Biosolids, including treated sewage sludge and waste from the food production industry, are routinely, and frequently, spread on agricultural fields as fertilizer.

Biosolids, including treated sewage sludge and waste from the food production industry, are routinely, and frequently, spread on agricultural fields as fertilizer.

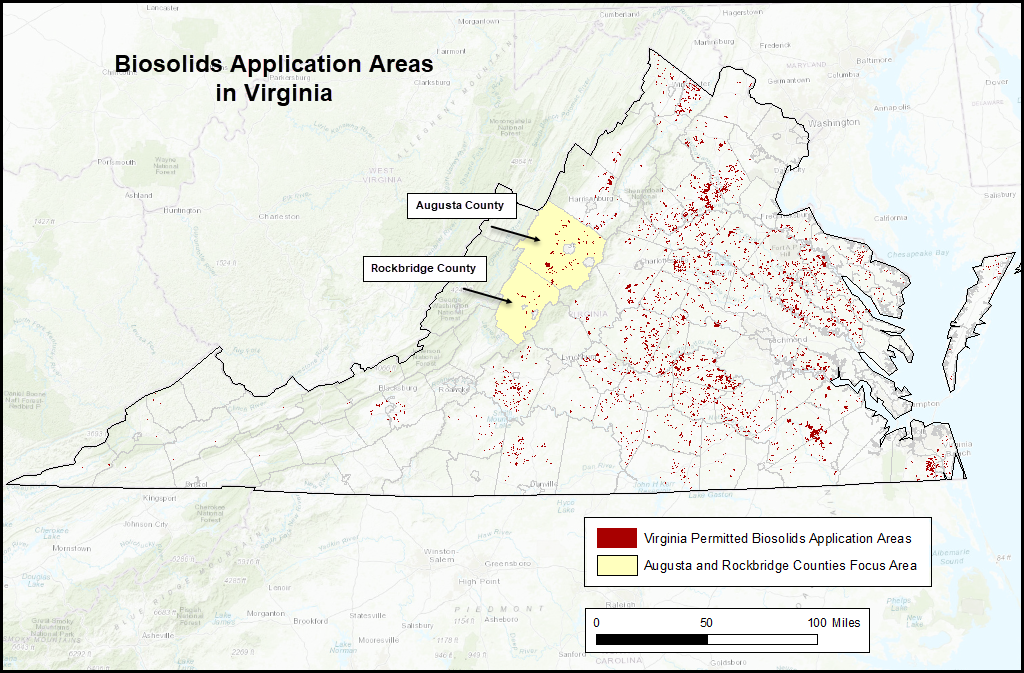

In Virginia, land application of biosolids has been managed by various agencies since the 1960’s. Currently it is managed by the Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ).

Though land application of biosolids has long been challenged as a threat to human and environmental health, the practice continues.

With thousands of potentially toxic chemicals in use across every facet of our society, few of which are captured or treated in wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs), many feel that land application of biosolids, here and across the county, needs another look.

“Emerging contaminants of concern”, such as PFAS, or “Forever Chemicals” are known to have negative human health effects and are NOT part of any testing regime for biosolids destined for land application in Virginia.

As of fall, 2022, there were over 9,600 locations in Virgina that are known to have received biosolids material. We believe this is since 2007, but it may go back farther…or there may be thousands more locations that are not mapped.

ABRA has focused on Augusta and Rockbridge counties to try and determine how the program works, what the data looks like, what is being tested and for what chemicals, and what are the results. Also…what is considered OK to put into our food chain? We’re still not entirely sure…but there has been a lot of it.

In Augusta and Rockbridge, between 2007 and 2022, 417 locations received biosolids. Some on many occasions. In all, there were over 6500 instances where biosolids were spread in those two counties. Extrapolate that to 9600 locations across Virginia and you start to see how much material is being applied to the land.

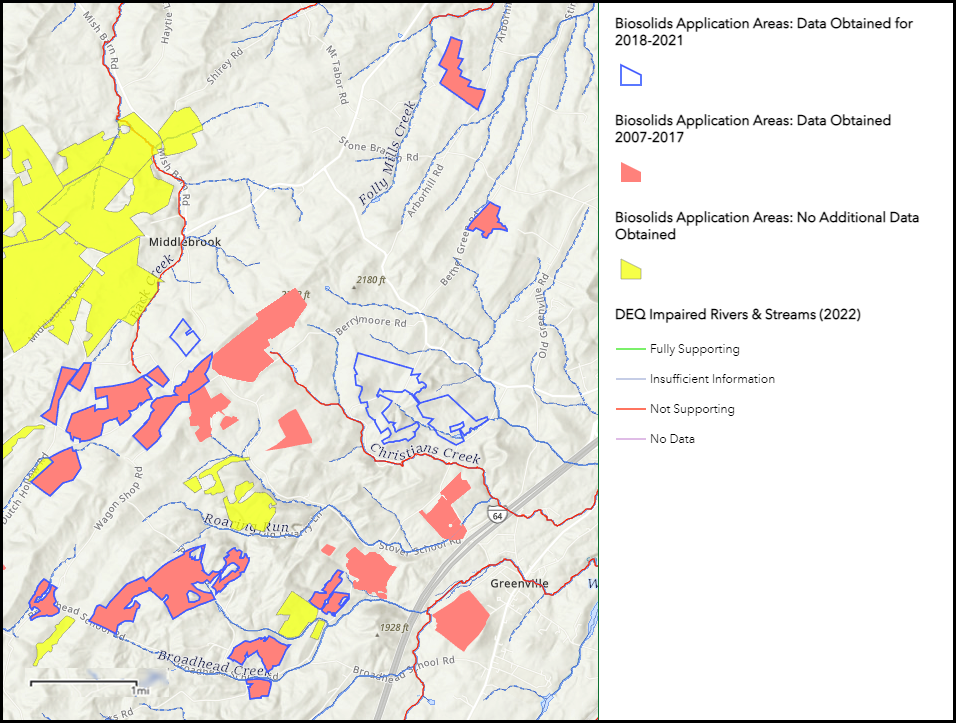

Due to data quality issues, ABRA was not able to match up all the locations in Augusta and Rockbridge to spreading events in the data that was received from DEQ. They themselves admitted the data is a mess. In this image, areas for which data don’t have geographic matches are shown in yellow.

The data is in poor shape. ABRA has obtained records going back to 2007, when DEQ took the program back over from the Department of Health. Earlier data is on paper, in boxes, in a storage unit somewhere.

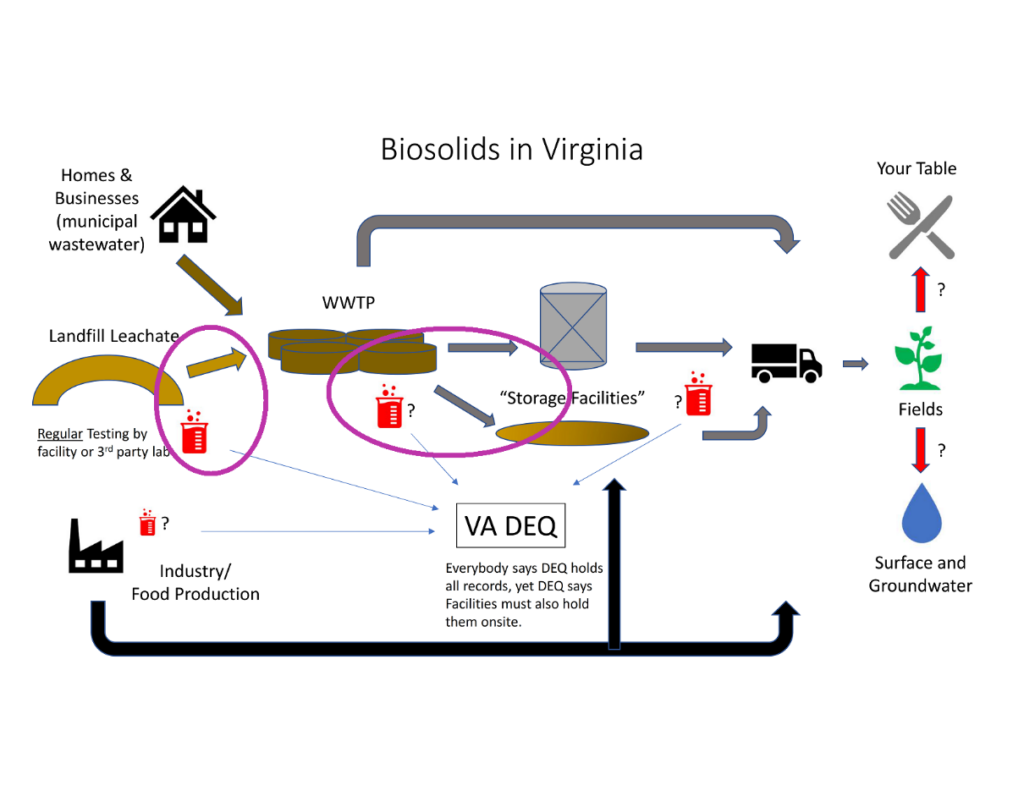

Material comes from households and the food industry, though landfill leachate may be treated in the same facilities.

The biosolids program works with several other separate programs, NPDES, Landfill design and permitting, certifications of private “land appliers”, etc. Though testing occurs in some locations in the waste stream, nobody is testing for PFAS, or anything other than heavy metals and pathogens. Untangling which program is responsible for what testing, data, design parameters, etc. has been difficult, though the DEQ staff managing the biosolids program have been helpful.

ABRA has determined two points in the biosolids material-handling process where testing already occurs. These present an opportunity to add testing for additional contaminants of concern.

Landfill leachate, often processed by WWTPs, is already tested regularly, but not for PFAS. Testing this material for these and other contaminants should be required. Some landfills pipe their leachate directly and continuously to a WWTP, and simply test the leachate on a regular basis. This should stop, and holding tanks should be added to allow for testing turn-around. Other landfills send leachate to WWTPs by truck, a process which also could support a testing period. Some landfills simply re-apply leachate to the top of the landfill in an endless cycle.

Biosolids material coming out of WWTPs is already tested for metals and pathogens, and often goes into storage facilities before being spread. Additional testing should be added here, before new material is mixed in with whatever is already in the storage facility.

These seem like obvious and relatively easy places to increase our ability to see what is going onto our fields, and into our water and our food via the biosolids pathway.

ABRA is still working to make sense of this program. We will update this page and the interactive map as we learn more.